Book review - Artificial intelligence meets natural stupidity by Drew McDermott and Computing taste by Nick Seaver

psychology AI books language Incidentally reading the paper (no it is not actually a book) by McDermott and finishing Computing taste by Seaver, I decided to rather quickly than comprehensively write up a summary review of both.

Review of Artificial intelligence meets natural stupidity by Drew McDermott, 1976

The overarching topic is, that many or most of the issues raised in this article are still helpful and relevantly unresolved, when looking at contemporary AI.

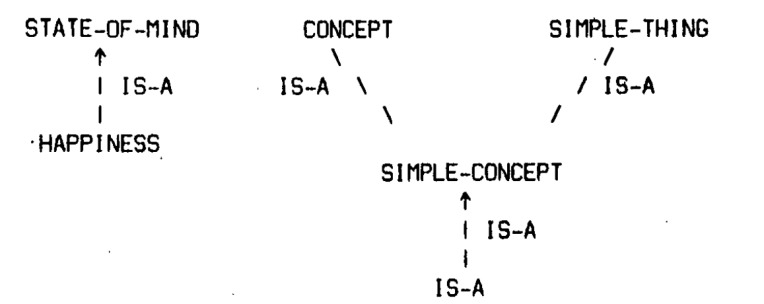

One item is, that just because I name my program

intelligent-program, that does not mean that it is intelligent.

Another item is an invitation to get to terms with the intricacies of language. Stochastic parrots do not understand how language is connected to the processes and events it refers to anymore than an n-gram model does.

The third item is about how progress in AI is often impeded by the speculation-after-implementation phenomenon, found in PhD theses. It leads to a state where problems that are really unsolved appear as if they are solved for future students picking topics, and thus left untouched thereafter. The claim is, that if an implementation would be accepted for getting a PhD awarded, and the thesis text would focus on the failure analysis of this one single implementation, it would be beneficial for the actual development of the field.

This article is a very entertaining read. Do not get scared by the number of pages, one third of it is references and each page is short. Highly recommended regarding its entertainment value and some insights on the intricacies and everyday hickups when dealing with language and that starts with words like ‘a’, ‘the’, and ‘is’.

Some selected quotes

p7/p15/156: [natural language yes, but first understand what language is]

In this section ] ‘have been harsh toward A[’s tendency to oversimplify or overglorify natural language, but don’t think that my opinion is that research in this area is futile. |ndeed, probably because ] am an academic verbalizer, ! feel that understanding natural language is the most fascinating and important research goal we have in the long run. But it deserves more attention from a theoretical point of view before we rush off and throw together “natural-language” interfaces to programs with inadequate depth. We should do more studies of what language is for, and we should develop complex programs with a need to talk, before we put the two together.

[I leave the OCR errors in there to emphasize the point with your pleasure.]

p8/p15/156 - p16/157:

The idea is formally pretty and seems to mesh smoothly with the way a rational program ought to think. Let us call it !’sidetracking control structure” for concreteness. The researcher immediately implements an elegant program embodying automatic sidetracking, with an eye toward applying it to his original problem. As always, implementation takes much longer than expected, but matters are basically tidy.

p8/p17/158: phd theses: if a mere implementation of version I

The solution is obvious: insist that people report on Version I (or possibly “| 1/2”). If a thorough report on a mere actual implementation were required, or even allowed, as a Ph.D. thesis, progress would appear slower, but it would be real.

p8/p17/158

When a program does fail, it should tell the explorer why it failed by behavior more illuminating than, e.g., going into an infinite loop.

p9/p19/160: the wishful control structure

The idea that because you can see your way through a problem space, your program can: the “wishful control structure” problem.

Sources

- p7 to p9 refs refer to version https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234784524_Artificial_Intelligence_meets_natural_stupidity

- p15/156 to p19/160 refs refer to version https://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/irm/mcdermott.pdf

Review of Computing taste by Nick Seaver

A social anthropology of people comprising the music recommender systems scene. What is the mindset of people designing and building these systems?

In 2023 recommender systems are deployed pervasively and while this book is specifically about music recommender systems, a great deal of their logic and culture probably is relevant to the entirety of contemporary internet reality on Amazon, Alibaba, Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok, Twitter, etc.

The book for a tiny flash of a moment starts sounding like a lot of uninformative verbiage, but it is entirely not so and it took me by surprise, twice.

Once, by unexpectedly useful analytical metaphors (traps, parks, and gardening), and then again by some unforeseen story turns.

It is just quite surprising how content based approaches enter the stage only in chapter 4. That is only due to the books narrative in the sense that it proceeds mostly chronologically. This means, music recommender systems only turned to the actual audio content at a late stage in their development, at least as seen from 2023.

Incidentally, I enjoyed the extended discussion of Every Noise At Once by Glenn McDonald. The fact that musicical genre space (as indexed by usage patterns) is not a flat space but has wormholes that shortcircuits some genre connections against hierarchical separation is nicely brought out.

There is one item in there which I appreciate particularly, called acoustemology, a portmanteau of acoustic and epistemology. Epistemology is about how we acquire knowledge about stuff. Acoustemology then means, how we acquire knowledge about stuff acoustically, that is, through hearing. Essentially, you will often start hearing it first, when your car starts having a problem.

I have this thing going in my robotics research which I call preverbal audio perception. Learning things about the world through hearing on a level fundamentally below language, parsing and understanding streams of words. I have always been puzzled by the general preoccupation with language as opposed to this analytical listening before there are words. It is not only much more interesting but also a prerequisite for language competence (that’s a hypothesis).

The pyramid of listeners was also particularly noteworthy and first seen here.

Thanks, great read.

Some selected quotes

Introduction: Technology with Humanity

Page 8

understand algorithms as the absence of a human hand didn’t make sense, because, as Ogle said, humans were everywhere: they wrote the code, they generated the data, they made the decisions about how a system should work.

Chapter 1 Too Much Music

Page 28

Overload was such a fixture of local common sense that it took me a long time to realize that it might not be a problem at all. Why should access to a large catalog be understood as a burden rather than a resource?

Page 35

The term “information overload” is commonly credited to the futurist consultant Alvin Toffler, who, in his 1970 book, Future Shock, made a dire forecast: as demands on their attention grew, fueled by new media technologies, people would “find their ability to think and act clearly impaired by the waves of information crashing into their senses” (354).

Page 36

In the mid- 1500s, scholars worried about the “confusing and harmful abundance of books” (Blair 2003, 11).

Chapter 2 Captivating Algorithms

Page 50

The ultimate measure of functionality, Mike explains to me, is “the hang- around factor”— what keeps listeners listening.

Page 50

But new users pose a challenge: data- driven recommendation requires data, and new users don’t have any.

53

“If it can’t be used for evil, it’s not a superpower.”

55

I use the term “captology” to refer to this broadly behaviorist common sense in the software industry,

55

There are many ways one might measure how well a recommender system works, but for most of the field’s history, one metric has dominated all others: predictive accuracy.

56

Researchers sometimes attributed RMSE’s paradigmatic status to the Netflix Prize, a contest run by the online movie rental company from 2006 to 2009 that offered a $ 1 million award for the first algorithm that could beat its existing system’s RMSE by 10 percent. 8 Netflix provided a data set of about one hundred million ratings, including anonymized user IDs, movie titles, release dates, and the date each rating was made. Competitors could use this data to train their algorithms, trying to predict the ratings in the set as precisely as possible.

57

submitted by a team named BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos, had achieved an RMSE of 0.8567 and established the state of the art for predictive accuracy in collaborative filtering.

57

But the winning algorithm did not succeed by finding one particular technique that beat all others. Rather, as the contest went on, high- performing teams combined their efforts and models together into ensembles that essentially blended the outputs of a set of algorithms. BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos was a combination of teams named BellKor, Pragmatic Theory, and BigChaos.

57

The second- place team, appropriately named the Ensemble, was an amalgam of twenty- three other teams.

57

After the Netflix Prize, it became common sense among recommender systems researchers that the best results were achieved by systems that blended together the outputs of many techniques, like the system Mike was building at Willow.

Chapter 3 What Are Listeners Like?

74

it required an explicit theory of listeners, their behavior, and their variation.

75

“What you tell us about what you like is far more predictive of what you will like in the future than anything else we’ve tried. . . . It seems almost dumb to say it, but you tell that to marketers sometimes and they look at you puzzled” (Gladwell 1999, 54).

75

Riedl and Konstan wrote a book together, Word of Mouse: The Marketing Power of Collaborative Filtering (2002),

76

In a 2018 press tour, for instance, Netflix executives described how the service orients itself toward a set of roughly two thousand data-derived “taste communities” because “demographics are not a good indicator of what people like to watch” (Lynch 2018).

78

“There’s a pyramid of listeners,” Peter told me (fig.

81

“It’s hard to recommend shitty music to people who want shitty music,”

Chapter 4 Hearing and Counting

96

these graduate students think that the idea of musical similarity, on which recommendation depends, is too vague to be scientifically evaluated. There are simply too many ways for music to be similar.

97

Today, most of the large ensemble models used for music recommendation include, in some way, a representation of sound, mixed in with the other data sources we’ve encountered so far.

97

“Sound, hearing, and voice mark a special bodily nexus for sensation and emotion because of their coordination of brain, nervous system, head, ear, chest, muscles, respiration, and breathing. . .

97

Feld (2015, 12) argues for attention to acoustemology—to “sound as a way of knowing,” which is contrasted with scientific approaches to studying sound. To know through sound is to know in an embodied, emplaced, and relational way

98

Many critics and practitioners have suggested that music recommendation might be improved by focusing on “music itself”—that is, how it sounds.

100

this spectacle is veiled from the material eye, we have another bodily organ, the ear, specially adapted to reveal it to us. This analyzes the interdigitation of the waves, . . . separates the several tones which compose it, and distinguishes the voices of men and women—even of individuals—the peculiar qualities of tone given out by each instrument, the rustling of the dresses, the footfalls of the walkers, and so on.”

102

“The time domain is for losers”

107

The sociologist Jennifer Lena (2012, 6), for instance, defines genres as “systems of orientations, expectations, and conventions that bind together industry, performers, critics, and fans in making what they identify as a distinctive sort of music.” Djent is defined not by the djent, but by the community of people like Tomas, who come together on web forums or at concerts and make the genre cohere. If this is what genre is, then it is unsurprising that algorithms working only from audio data would make mistakes that appall true fans

108

This problem, I learned, is called the “semantic gap”: there is a distance between the information encoded into an audio file and the meaning that an enculturated human mind can interpret from it. 2

Chapter 5 Space Is the Place

132

listeners might be surprised to discover that their “favorite” genre had a name that neither they nor the artists involved had ever heard of.

132

“I’m cheerfully unrigorous about what a genre can be,” McDonald said in an interview, “Some of them are musicological, some are historical, and others are regional themes.

133

While genre theorists might find it odd or incorrect to call “sleep” or “deep cello” genres, for people like McDonald, the term was essentially synonymous with “cluster.” Conventional genres simply served as a prototype for thinking about the many ways that similar music might be gathered together.

133

heard the same thing: “genre recognition”—a long-standing analytic task in which researchers tried to guess a song’s genre from its audio data—was being superseded by “tag prediction,” in which software would predict which labels users had assigned to tracks on music streaming platforms like SoundCloud.

135

The conquest of genre by similarity, strangely enough, results in a situation where artists may be part of a genre without realizing it;

137

postgenre artists

143

A band like Queen, for instance, might accidentally receive a boost in popularity if Whisper’s data scrapers mistook a news article about Queen Elizabeth II for one about the rock group.

Comments

tag cloud

robotics music AI books research psychology intelligence feed ethology computational startups sound jcl audio brain organization motivation models micro management jetpack funding dsp testing test synthesis sonfication smp scope risk principles musician motion mapping language gt fail exploration evolution epistemology digital decision datadriven computing computer-music complexity algorithms aesthetics wayfinding visualization tools theory temporal sustainability supercollider stuff sonic-art sonic-ambience society signal-processing self score robots robot-learning robot python pxp priors predictive policies philosophy perception organization-of-behavior open-world open-culture neuroscience networking network navigation movies minecraft midi message-passing measures math locomotion linux learning kpi internet init health hacker growth grounding graphical generative gaming games explanation event-representation embedding economy discrete development definitions cyberspace culture creativity computer compmus cognition business birds biology bio-inspiration android ai agents action